Stephen Few seems to be upset. In his yearly review, he touches on what sees as a year without any progress:

Since the advent of the computer (and before that the printing press, and before that writing, and before that language), data has always been BIG, and Data Science has existed at least since the time of Kepler. Something did happen last year that is noteworthy, however, but it isn’t praiseworthy: many organizations around the world invested heavily in information technologies that they either don’t need or don’t have the skills to use.

The terms “data science” and “big data” have long been debatable, not terms I feel strongly about, either. Somewhere, he misses even his own points:

Data sensemaking is hard work. It involves intelligence, discipline, and skill. What organizations must do to use data more effectively doesn’t come in a magical product and cannot be expressed as a marketing campaign with a catchy name, such as Big Data or Data Science.

Take the assumption that software is overblown and overinvested, the real missing component of research–or “data sensemaking”, because lets replace one made-up word with another–is the lack of human capital. The argument seems to be that the world needs both managers and staff who can wisely invest in analytical software and capable of carrying-out research.

Surely, then, it must be notable the increase in the number of programs focusing on the data analytics. These programs are spreading to nearly every discipline and cross-discipline into new areas. The University of Chicago’s M.S. in Computational Analysis and Public Policy is designed to train the next generation of researchers in government. If it involves intelligence, discipline, and skill, isn’t the growth of graduate programs a significant factor to raising the number, ubiquity, and quality of analytics that is capable on a day-to-day basis?

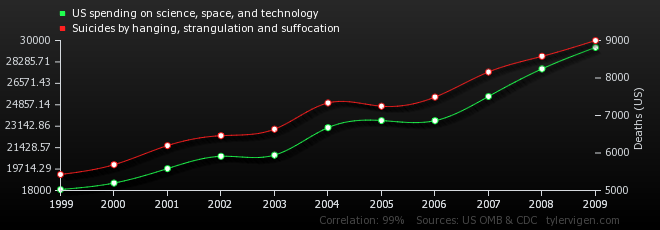

Notwithstanding the growth of these programs, the most memorable project from this past year highlights the dangers of blind correlation, a lesson that statistics teachers everywhere to avoid bad statistics. Tyler Vigen’s Spurious Correlations mines data sources to find strong correlations that are meaningless. We’ve been able to systematize and mass-replicate bad analytics that can be highlighted for others. At times, I wish I was teaching again so I can show this site to undergraduate students.

[caption id=”attachment_1943” align=”aligncenter” width=”660”] The spurious correlation between US spending on science, space, and technology

The spurious correlation between US spending on science, space, and technology

correlates with suicides by hanging, strangulation and suffocation[/caption]

The overuse of phrases like “big data” and “data science” is growing quickly and annoyingly. The answer to articles that ask ”Will X be the next big thing?” is usually “no”, the odds are against new things. Even recent articles on how statisticians can “tell correlation from causation” creates a hype around the discipline that is, well, hype. But it’s important to not be lost in the hype–or the frustration from hype–yourself. To be in this discipline, at this time, is quite noisy.

The term big data is meaningless and often leads to silly debates with no consistent answer. But, it is rather meaningful that we can scale queries horizontally across multiple computers. It’s even more meaningful since it’s quite cheap to do this across virtual machines over the internet–and I remember when LAN parties were fun. Overblown and inaccurate headlines on correlation and causation is frustrating, but it ultimately provides a novel approach on helping parse through large–dare I say, big?–amounts of data. Likewise, the continuing adoption of good programming techniques into code written by statisticians has improved the entire discipline. These practices are spreading and being institutionalized in universities and accelerated training programs.

Calling a year a loss because constant praises of ”big”, “behemoth”, or “slight-larger-than-average” data is succumbing to the same gloss that the marketing gimmicks are selling.