I’ve often found myself exploring a library’s map room or thumbing through old Census records while taking study breaks. I was often surprised how I could become engrossed with old data. Some of the fascination comes from a historical narrative of history from the perspective of that generations point-of-view, even if it was based on faulty logic or data that would be later crystalized. With the advent of open data, digital maps, and databases, how will we be able to explore historical data in the future; that is, how can we look at today’s data over the next 20 years?

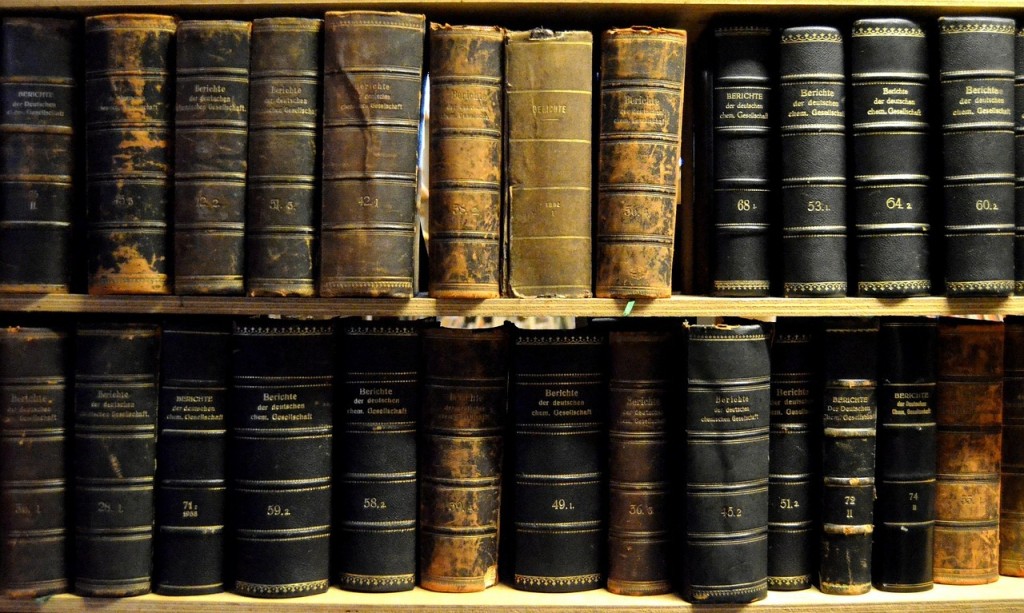

[caption id=”attachment_1993” align=”aligncenter” width=”640”] They lack machine-readability, but they do have longevity[/caption]

They lack machine-readability, but they do have longevity[/caption]

The paradox is paper documents are not easily accessible and shunned by the open data community, but paper has proven to be one of the most accessible formats across generations while digital formats are frequently deprecated and takes a higher level of expertise to open. As a result, today’s open data portals provide up-to-date, machine-readable data, but how will this impact the next generation who wants to read the same data?

Open data portals will be the proverbial map room for the next generation. Have we done well enough to preserve this data for tomorrow’s investigators of history? Often, the process on updating today’s data portals are not tuned to long-term preservation. For instance, maps are updated frequently, but often, updated information is simply overwritten historical data. Even tabular data may be rewritten with the most recent information and older data, even if inaccurate, is lost to the digital recycle bin. Immediately updating information is very useful for contemporary purposes such as transparency and app development. What are the ramifications of this process for the next generation, who will rely on this digital data and not paper-based maps?

Maintaining historical data is one thing, but we need to be mindful of providing formats that can be opened by future users. Vint Cerf recently noted an internet “dark age”, where today’s memories, data, and pictures won’t be accessible to future generations. This is also true for open data, where today’s maps and data are not guaranteed to last or be easily accessible for tomorrow. While it’s possible to convert file formats, this requires more expertise by the end-users, potentially dissuading future researchers. Moreover, what happens when portals grow, transform, and change? It seems likely that data may be eventually purged and deleted – essentially the same problem of the lost floppy disks of data from the 1990s.

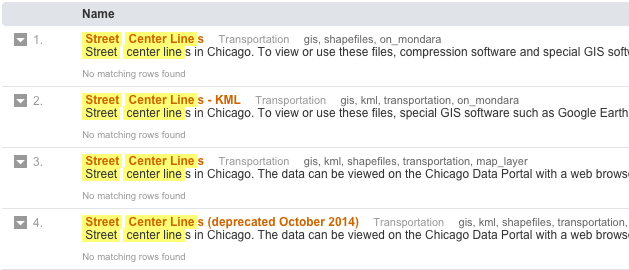

Chicago’s open data team has identified this concern as well, beginning to take some limited measures to counteract these problems. Most notably, we instituted some limited version control of maps. New maps aren’t overwritten, but deprecated. Take, for example, uploads of the city’s Street Center Line data that shows the location of all Chicago’s roads. Deprecated files allow those interested in older data to see how Chicago’s roads have grown and changed over the years.

Yet, this isn’t a tenable solution. This process works on a limited basis, but would not work on data that changes frequently.

Libraries themselves may be able to provide the most help on this problem. Libraries have been experts on preservation for decades, which has also extended to digital preservation, such as the University of Chicago’s digitization of old maps. Digital preservation for already-digital data is a different practice. This practice requires frequently changing data to be captured. Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine accomplishes this by preserving websites over time, but archiving open data needs to preserve the data formats and any links directed to metadata.

This topic deserves far more conversation, but here are some initial thoughts on how to counteract these issues:

- Use open formats that are more likely to evolve as they are less dependent on companies that drive proprietary formats. Open formats are more likely to have conversion tools.

- Libraries have been the preservationists for generations. We can adopt those practices for digital preservation, working with libraries to develop practices that preserve digital data.

- Encourage greater version control of open data. While some practices can be adopted (see above), these are kluge and will be difficult to manage over decades.

- Reduce the practice of overwriting data, making a dataset a historical and contemporary records.

Digital preservation is one of the items that needs to be addressed as data portals mature. For now, time is a little on our side, but not for much longer.